Over at the Huffington Post Stephen Zunes writes about how the WikiLeaks cables illuminate the role of ideology in Washington’s approach to Western Sahara, with a pretty damning verdict on the ex US ambassador to Morocco (now in Cameroon), Robert P Jackson. However, beyond Zunes’ analysis and a few blog posts here and there, what the leaked cables have to say about Western Sahara has, unsurprisingly, received little attention. So, here is an attempt to plug the gap. I’ll try and expand/augment this post in due course, when time permits.

The discussion below is based on two cables circulated by Spanish daily El Pais, and three cables posted by the Lebanese newspaper Al-Akhbar (whose website is down as I write this). The latter are from a batch of nearly 200 cables obtained by Al -Akhbar from a source other than WikiLeaks, according to The Atlantic, which concludes that the cables are most likely genuine. Of course we have to entertain the possibility that they are not, although this seems remote. The cables discussed here date back to 2006 – those prior to 2009 (all but one) were sent when the last Bush administration was in power. I’ve included links to the cables available on the El Pais website. However, as the Al-Akhbar site is currently down, and the other cables do not appear to be available elsewhere, no links can be provided for these at the present time (I’m working from versions printed before the site went down). Some cables released by Al-Akhbar are available elsewhere, such as these from the Algerian embassy.

The cables cover a number of themes, around which the discussion below is organized. Cables are identified by a code indicating the year (first two characters), the place of origin (in this case Rabat and Casablanca), and the number of the cable.

Autonomy/MINURSO: pressure and protection

Cable 06RABAT678 describes a meeting with Taieb Fassi Fihri, Minister-Delegate of the Moroccan Ministry of Foreign Affairs, where Morocco’s autonomy plan for Western Sahara was discussed. The tone of the cable is very much one that emphasises what it calls the “difficulty” of Morocco’s position, and Fassi Fihri acknowledged that the Polisario and Algeria are “probably not willing to discuss” the autonomy plan. One thing that is particularly notable in this cable is the statement that “Fassi Fihri wanted to be assured that the US would continue to support MINURSO even if a credible autonomy plan is not submitted in a timely manner.” The US ambassador is reported to have responded that “engagement between Morocco and other actors is necessary and that a substantive autonomy plan and implementation plan must be submitted or there will be no support for a MINURSO extension.”

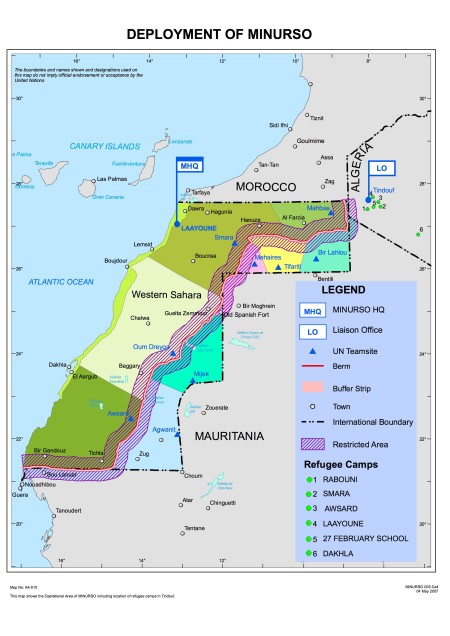

Two conclusions may be drawn from the above. First, Morocco sees the MINURSO presence in Western Sahara as in its interests. This will come as no surprise to those who conclude that one of the main roles that MINURSO has played has been to freeze the conflict while Morocco entrenches its position in Western Sahara. Morocco’s desire to keep MINURSO in Western Sahara is deeply ironic, given Morocco’s insistence that the referendum that MINURSO is mandated to arrange will never take place. For those unfamiliar with the situation in Western Sahara it’s worth pointing out that MINURSO stands for United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara. Second, the US put pressure on Morocco to move forward with the autonomy plan, egging Morocco on in the legitimization of its occupation of Western Sahara.

Corruption: occupation as opportunity

Cable 08RABAT727 addresses corruption in the Moroccan military, which is described as widespread (the term “plagued” is used liberally). The cable claims that “Lt Gen. Bennani [commander of the forces in Western Sahara] is using his post to skim money from military contracts and to influence business decisions”, and that it is rumoured that he owns a large part of the fisheries in Western Sahara. This situation is seen as symptomatic of the legacy of Hassan II’s deal with the military, which is characterised as “remain loyal, and you can profit” (historically, fear of a coup against appears to be one of the main determinants of the palace’s relationship with the military). In this context, the Western Sahara command is apparently seen as particularly lucrative and jealously guarded by a few families within the military. Outside of the military, cable 09CASABLANCA226 concludes that corruption in the real estate sector is increasing rather than diminishing.

Security and Terror: spectres and diversions

The leaked cables highlight Morocco’s strategy of playing the security card in order to bolster its position in Western Sahara, but also illustrate that they are overplaying their hand here.

Cable 09RABAT479 describes how Mustapha Mansouri, President of the Chamber of Deputies, “feared that the loss of Western Sahara would open a vast, anarchic ungoverned space, with no real borders extending thousands if miles east from the Atlantic. Only Western Sahara, under Morocco’s control, was an exception.” Mansouri used some of the arguments beloved of the commenters on this blog, particularly our old friend Ahmed Salem Amr Khaddad, to characterise the conflict. He “said that the conflict was really a legacy of the Cold War and of Algeria’s continued attachment to Eastern, socialist models.” Mansouri reiterated the Moroccan position regarding the UN mandated referendum in Western Sahara, that “self-determination could mean autonomy or integration but not independence.” As usual, Morocco believes that self-determination for the people of Western Sahara means something determined by outsiders in Rabat. No further comment should really be necessary here.

[The above cable was sent in the context of visit by a number of US Senators, led by Senator Richard Burr, to Morocco. The cable concludes by saying that the Senators “learned more about Western Sahara”, and Burr “assured Mansouri that he would be welcomed on Capitol Hill.”]

Cable 8RABAT150 covers some similar themes, and describes a meeting with Mohamed Yassine Mansouri (no relation to the Mustapha Mansouri mentioned above), chief of Morocco’s external intelligence service. This Mansouri echoed his namesake, saying that “no Maghreb country, with the possible exception of Morocco, can begin to control its frontiers.” On the Polisario, Mansouri did his best to have it both ways, saying that “the terrorist threat there is real”, while being “very careful to say that the GOM [Government of Morocco] does not think the POLISARIO is a terrorist organization.” However, he did claim that

“…some members of the POLISARIO have joined AQIM [Al Qa’ida in the Lands of the Islamic Maghreb]. Morocco is particularly concerned that should Algeria and the POLISARIO install themselves outside the berm in the no man’s land in Western Sahara, this could become a base for terrorist training and operations, which Morocco could not tolerate.”

We can only presume that Mansouri was engaging in the old Moroccan trick of deliberately confusing the 5 km buffer strip on the east and south of the berm (the only part of Western Sahara that might be described as a “no man’s land”) with the extensive area under Polisario control that, like the considerable large area controlled by Morocco, is designated as an “area with limited restrictions” under the terms of the 1991 UN-brokered ceasefire agreement. This, again, is a favourite tactic by Morocco, which seems desperate to deny the reality that Western Sahara is actually partitioned, with the areas controlled by Morocco and the Polisario having parity of status under the terms of the ceasefire, and therefore in international law (see earlier posts here and here). To acknowledge this fact would be to admit that all its autonomy plan will do is legitimize a partial occupation of Western Sahara, without actually resolving the conflict. As for members of the Polisario joining AQIM, well, show us the evidence. To those of us who have interacted with the Polisario this seems unlikely, to say the least. The Polisario leadership would be very unlikely to tolerate any such conversion, given its fears of radicalization among the population of the refugee camps and its concerns about its international reputation and image.

Cable 08RABAT727 rather deflates Mansouri’s claims, exhibiting a clear understanding of the geopolitical realities in Western Sahara as it talks about Polisario’s “small, lightly armed presence at a few desert crossroads in the small remaining part of Western Sahara outside the berm.” It goes on to say that

“the GOM [govt. of Morocco] almost certainly is fully conscious that the POLISARIO poses no current threat that could not be effectively countered. The POLISARIO has generally refrained from classic terrorist bombings, etc. Although the specter is sometimes raised, there is no indication of any Salafist/Al Qaeda activity among the indigenous Sahrawi population.”

Talking of radicalization, Morocco’s obsession with the “empty spaces” of the Sahara, and with the alleged terrorist threat posed by any settlement of the Western Sahara conflict not in its favour, is put in perspective by the very real and demonstrable radicalization of Moroccans inside Morocco. Cable 8RABAT150 describes how Minister of the Interior Chakib Benmoussa “pointed out that approximately 60 Moroccans had been arrested before they could depart Morocco” for Iraq, and that another 70 were “being watched and/or sought in the country and the region.” Morocco’s external intelligence service “noted that 139 Moroccan foreign fighters had attempted to go to Iraq since 2003,” with a “resurgence in the foreign fighter pipeline in 2006”. 40 Moroccans “had definitely reached Iraq, and 38 of them had participated in suicide missions.” The intelligence service also noted that “Moroccan cells cooperated with individuals and cells in Denmark, Sweden, Span, Saudi Arabia and Syria.” The Foreign Minister “lamented that potential extremists pay too much attention to al-Jazeera,” something that might not be a problem now, since Morocco kicked them out of the country for being too critical of the Moroccan government.

Cable 08RABAT727 briefly touches on the issue of home-grown militancy, stating that “reporting suggests small numbers of FAR soldiers remains [sic] susceptible to Islamic radicalization”, and reminding readers that those behind the 2003 Casablanca bombings included members of the Moroccan military. Following the 2003 bombings, “Morocco’s internal security services have identified and apprehended several military and gendarmerie personnel in other terrorist cells, some of whom had stolen weapons from their bases for terrorism.”

A number of the cables highlight Morocco’s concerns (real or contrived) about Mauritania’s stability, and cable 8RABAT150 reports that Morocco’s external intelligence chief Mansouri argued that “Mauritania’s stability was more important than democracy”. To the Embassy staff’s credit, they responded that they believed it was possible to have both stability and democracy in Mauritania.

The main conclusion to be drawn here is that, while Morocco is keen to see terrorist threats in Western Sahara and among the Polisario and Sahrawi, the real terrorist threats to the Moroccan state are emanating from Morocco itself, and Morocco is playing a significant de facto role in the export of militant Islam.

Deployment: massively committed, thinly stretched, and poorly prepared

Cable 08RABAT727 claims that the Moroccan armed forces (Forces Armées Royales, or FAR) are preoccupied with Western Sahara, with some 50-70% of its strength deployed there at any given time. However, the FAR are reported to be stretched thin in Western Sahara, with operational readiness estimated at 40%.

Posted by Nick Brooks

Posted by Nick Brooks