Nick Brooks

You may or may not have heard that the ceasefire that has held for nearly 30 years in Western Sahara broke down yesterday, and the territory is now at war again. There is nothing on the BBC news website about it at the time of writing, although it did get a brief mention on the World Service and there is this article from the New York Times.

Both sides in the conflict – Morocco and the Polisario – have their versions of what’s happened, and Morocco is likely to have the loudest voice. So here’s my take.

Morocco invaded Western Sahara in 1975, when Spain pulled out. The Polisario, formed a few years earlier to fight for independence from Spain, opposed Morocco’s occupation. A war was fought until 1991, when the UN brokered a ceasefire and installed a peacekeeping force – the United Nations Mission for the Referendum in Western Sahara, known by its French acronym, MINURSO. As the name indicates, this force was mandated to organise a referendum on self-determination. This has never happened, and MINURSO remains the only peacekeeping force without a human rights monitoring mandate. Western Sahara remains a non self-governing territory as defined by the UN Committee on Decolonisation. In other words, the decolonisation process has not yet been competed. Western Sahara is often referred to as the Last Colony in Africa.

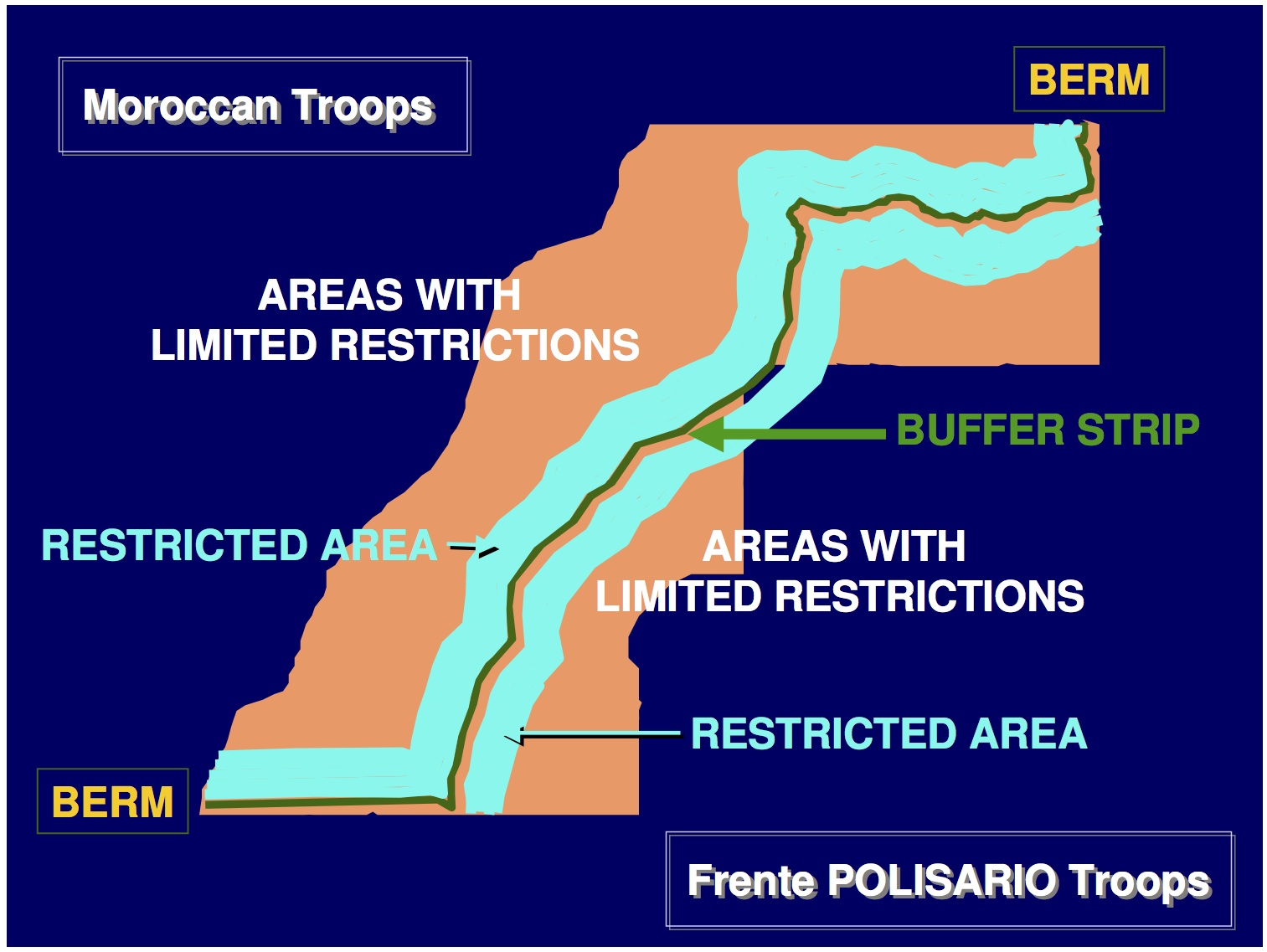

Throughout the 1975-1991 conflict, Morocco secured territory it had taken behind defensive earthworks or berms. By 1991, these had merged into a single structure – The Berm – which stretches 2700km (about 1700 miles) across the territory, effectively partitioning it into a Moroccan controlled zone to the west and north, and a Polisario controlled zone to the east and south (Figure 1). A detailed analysis of the Berm and its evolution is provided by Garfi (2014).

Under the terms of the ceasefire, Western Sahara is divided into three areas (Figure 1):

i) a Buffer Strip extending for 5km east and south of the Berm on the Polisario side, which is effectively an exclusion zone or no-man’s land, in which no military personnel or equipment are permitted;

ii) two Restricted Areas, extending for 30km either side of the Berm, in which military activities are prohibited; and

iii) two Areas with Limited Restrictions, which include all the remaining territory of Western Sahara, in which normal military activities can be carried out with the exception of those that represent an escalation of the military situation.

The above information, including maps showing the different zones and the text of the ceasefire (Military Agreement #1) used to be on the MINURSO website but were removed some years ago. When asked, MINURSO and UN Peacekeeping would not explain why, leading many to conclude this was a result of Moroccan lobbying. Morocco’s narrative is that it controls all of Western Sahara except a buffer strip established by the UN for its protection, and that the Polisario has no presence in Western Sahara. The maps and military agreement clearly contradict this.

Since 1991, Morocco has been entrenching its occupation of Western Sahara and developing its natural resources, against international conventions that prohibit occupying powers from exploiting resources in occupied territories for their own gain. These resources include phosphates, fisheries and water resources – Morocco has developed agriculture in occupied Western Sahara, including the production of water-intensive crops such as tomatoes (including the Azera brand).

Some of these resources and the products derived from them transit through Mauritania to the south, for example, fish products from occupied Western Saharan waters that are destined for African markets via the port of Nouadhibouin Mauritania. This route involves traffic passing through the Berm south of the settlement of Guergerat (Figure 3), then traversing the buffer strip for 5km to the border with Mauritania (Figure 4).

In late October 2020, Sahrawi protestors started blockading the road between the Guergerat Berm crossing and the Mauritanian border (Figure 4), within the Buffer Strip. They were protesting against the export of natural resources, including fish destined for the Mauritanian port of Nouadhibou, from occupied Western Sahara by Morocco. They also accused Morocco of facilitating the trafficking of drugs and people via Guergerat.

On 12th/13th November, Morocco sent troops to disperse the protestors and take control of the section of road traversing the Buffer Strip. By merely entering the Buffer Strip, Morocco breached the ceasefire. On 13th November, the Polisario declared that this breach marked the end of the ceasefire and the resumption of hostilities, and that they were now at war with Morocco. Later on the 13th, Morocco reported clashes along the Berm in the north of Western Sahara, and on the 14th it appeared that fighting was taking place in the vicinity of Mahbes and Hauza in the north of Western Sahara, and Aouserd and Guergerat in the south.

This all comes against a background of 45 years of conflict and exile for the Sahrawi. Somewhere around 100,000 Sahrawi live under Moroccan occupation, while perhaps around 200,000 live in five refugee camps in the Algerian desert around the town of Tindouf. These camps are governed by the Polisario, and are effectively a society and state in exile. The Polisario also controls the areas to the east and south of the Berm, known to the Sahrawi as the Free Zone.

For decades, discontent in the camps has been growing, particularly among younger Sahrawis, in response to the stalemate, the failure of the UN to organise the long-promised referendum, and an understandable perception that they have been forgotten and abandoned by the rest of world. Many see a return to war as the only way of having any hope of resolving the conflict, whether through military means or as the result of diplomacy facilitated by what they hope will be a renewed spotlight on the territory if hostilities resume. For many years, the Polisario has managed to keep this discontent contained and has avoided conflict. It seems that the latest provocation by Morocco has been too flagrant for this approach to remain viable.

Nick Brooks has travelled extensively in Western Sahara, as co-director of the Western Sahara Project, a research project focusing on archaeology and past environmental change in the territory. Between 2002 and 2009 he led six seasons of fieldwork in the Polisario-controlled zone of Western Sahara, and travelled to the territory on seven occasions, also spending time in the Sahrawi refugee camps around Tindouf. Fieldwork involved frequent detours into Mauritania to avoid the Moroccan Berm.

@SAHARAWIVOICE on Twitter is a good source of updates on the conflict.

Posted by Nick Brooks

Posted by Nick Brooks