The May 31st edition of Spiegel Online carries an article by Daniel Steinvorth with the title “Peace for the Big Sandbox: Western Sahara Eyes a Hopeful Future”, which extols the virtues of Morocco’s “autonomy” plan for the territory it invaded in 1975. This article is worth some comment in the context of Morocco’s ongoing push to gain acceptance for its autonomy proposals, which it has been touting around the world’s capitals for the past few months. Morocco’s allies across the globe have been mobilizing to explain the virtues of normalizing Morocco’s occupation of Western Sahara, a region designated by the United Nations as a “non self-governing territory” whose status is yet to be determined, and where the issue is one of decolonization. The UN has declared that the future of Western Sahara should be determined by a referendum which includes the option of full independence for its inhabitants.

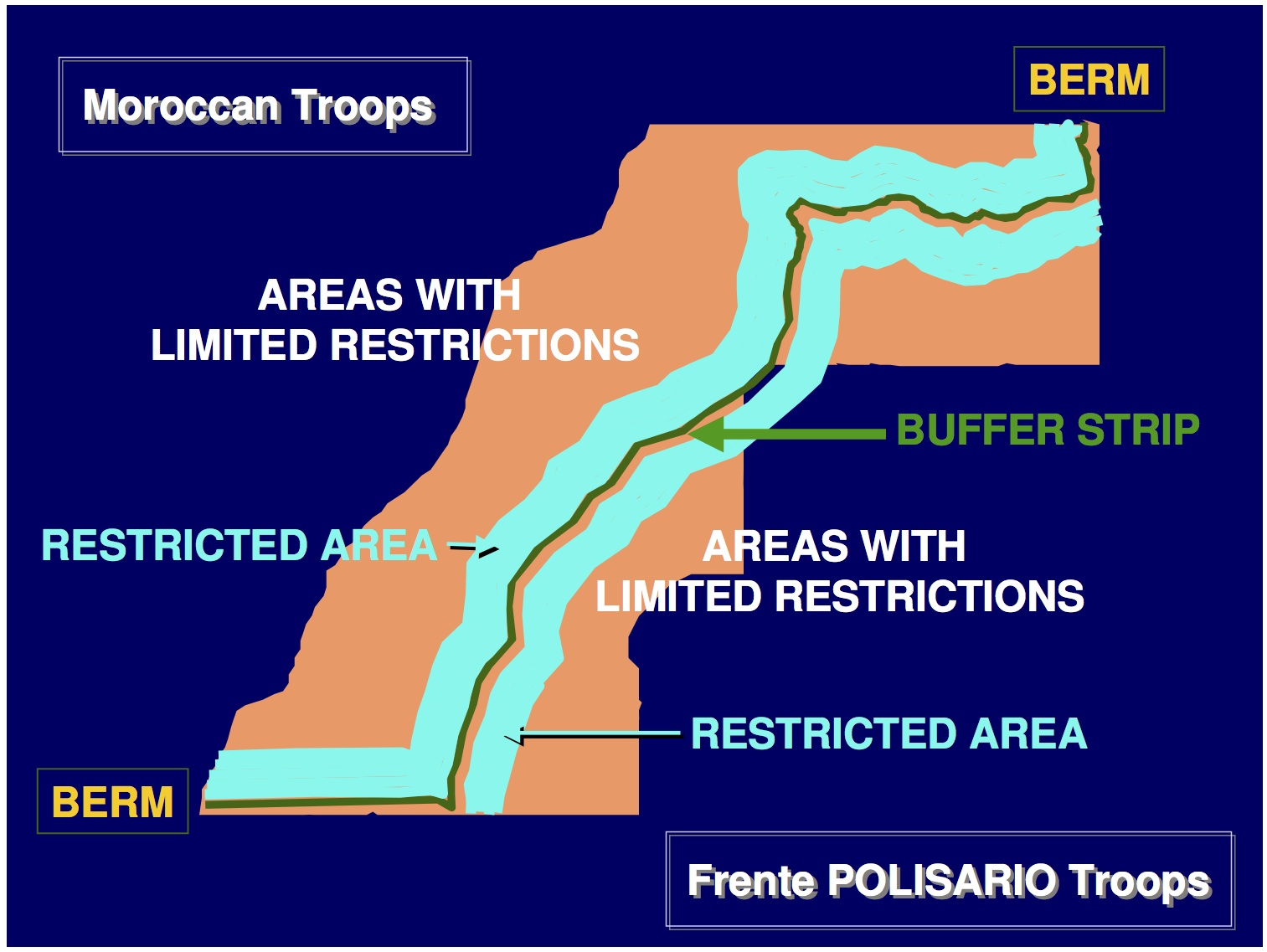

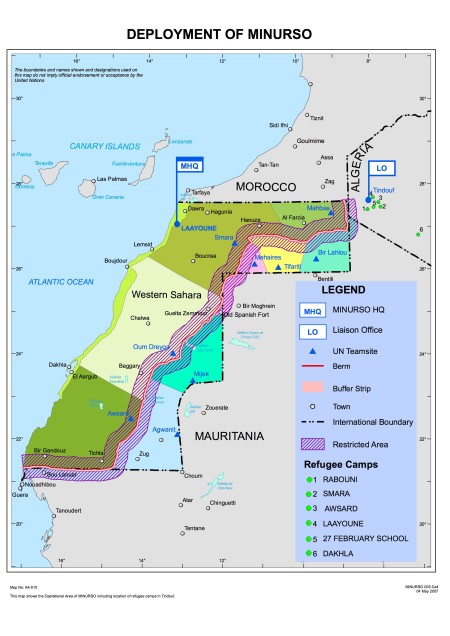

For some time now the Polisario independence movement, based in the little discussed “Free Zone” and headquatered in the Sahrawi refugee camps in neighbouring Algeria, has endorsed the idea of a referendum offering a choice between full integration into the Moroccan state, autonomy within a greater Morocco, or full independence. Morocco is now receiving much praise for offering a referendum on the future of Western Sahara, but the Moroccan plan does not include the independence option. Since the UN brokered a ceasefire in 1991 its observer force, known by its acronym MINURSO, has been ostensibly trying to organise a referendum on self determination, as required by UN Security Council resolutions 621 of 1988 and 690 of 1991. “Ostensibly” because, according to some observers, MINURSO and the UN have taken a somewhat indulgent position towards Morocco, which has engaged in obfuscation regarding arguments over voter eligibility (1). Morocco has done everything in its power to prolong the stalemate as it digs itself in behind the 1500 mile long wall of defensive earthworks (known locally as the Berm) with which it has partitioned Western Sahara, in order to keep the Polisario out of the areas it occupies. Morocco has also encouraged poor Moroccans to settle in occupied Western Sahara, offering financial incentives to those prepared to relocate. Some 200,000 or more settlers (plus some 160,000 troops) now outnumber the approximately 90,000 indigenous Sahrawi who remained in the territory after the Moroccan invasion.

So, what does Speigel Online writer Steinvorth have to say about the prospects for this divided territory, in which the principle of self-determination has been systematically undermined for so long? The article opens by introducing us to the Mayor of el-Ayoun, a member of “The Royal Advisory Council for Saharan Affairs” who, we are told, was instrumental in developing the autonomy plan. The Mayor gushes about how autonomy will solve all the territory’s problems and end the conflict between Morocco and the Polisario independence movement. Of course the Royal Advisory Council was set up by Morocco and is populated by Sahrawi living in the occupied territories who are sympathetic to the Moroccan position. While some Sahrawi living in occupation do see the most sensible option as integration with or limited autonomy within Morocco, many more do not, as apparent from frequent clashes between Sahrawi protestors and Moroccan police and security forces in occupied Western Sahara and also in Morocco itself.

Above a map showing the faintest of borders between Morocco and Western Sahara, Steinvorth tells us of the Green March, during which “350,000 subjects of then King Hassan II, armed with nothing but the green flags of Islam”, laid claim to the Western Sahara by marching into it from Morocco. Nothing is said of the parallel military invasion of the territory, during which tens of thousands of people were displaced into neighbouring Algeria. Survivors of this migration tell of how the Moroccan air force used napalm on fleeing refugees. The displaced Sahrawi still live in camps in the Algerian desert, whose population has been estimated by a number of independent bodies at somewhere between 160,000 and 200,000 (more of this later).

There follows an airing of the views of Moroccan Interior Minister Chakib Benmoussa, who, we are told, believes that the question of who should have sovereignty over Western Sahara is “the wrong question to ask.” Thanks for putting us straight on that one. Benmoussa repeats the often heard claim that the Sahara is a nest of terrorism, full of terrorist training camps and a conduit for terrorist weapons. We are told that European security is at stake, that European and American diplomats believe that Morocco can contribute to regional stability, and that “Western intelligence agencies believe that the no-man’s land between Algeria, Mali and Mauritania is a haven for Islamist terrorists.” The author then tells us that the same agencies believe that an independent Western Sahara “might be too weak to protect itself against terrorism emanating from the region.”

So there we have it, spelled out for us loud and clear. For the sake of international security we have to normalise Morocco’s occupation and annexation of a large swathe of a neighbouring territory, and ignore UN resolutions and the principle of self-determination. In short, we have to endorse a new phase of colonialism in Africa in order to secure our own safety. The argument that Moroccan aggression should be rewarded in the name of fighting the War on Terror is heard a lot from Morocco and its foreign apologists (2), and is worth some comment.

For some time, western intelligence agencies have been concerned that the “empty spaces” of the Sahara might provide a haven for terrorist groups such as al-Qaeda. The US is so concerned that it has sent troops to the region to help governments fight “terrorism” and secure their borders (a move that isn’t so beneficial for the pastoralists whose livelihoods involve regular informal border crossings in search of water and pasture).

However, the terrorist bogey in the Sahara appears to be essentially non-existent. While all North African countries have wrestled with militant “Islamism”, this has largely involved home-grown groups bent on overthrowing domestic governments. In Algeria’s case, Islamist terrorism was part of what was essentially a civil war precipitated by the annulment of election results that the Algerian military and the West didn’t like. This conflict played itself out mostly in the heavily populated Mediterranean coastal region, leaving the vast area of southern, Saharan Algeria largely unscathed. Even at the hight of Algeria’s troubles tourists were travelling in relative safety in the south. The more recent kidnapping of a group of German tourists in southern Algeria appears to have had nothing to do with terrorism, and is more likely to have been a political stunt aimed at justifying western support for “anti-terrorist” measures (requiring financial and material support) in Algeria. The author and North African expert Jeremy Keenan has written extensively on the exploitation of the “War on Terror” by North African governments, who have been conjuring up the Saharan terrorist bogey in order to secure military and financial aid. The Sahara has its share of bandits and smugglers, and when you hear about a terrorist incident in the Sahara the chances are that it involved a shoot-out between government forces and petty criminals, or that it was a put-up job by a North African government intent on scaring the west into providing it with money or weapons. The one place where these kinds of incidents are unheard of is actually the so-called “Free Zone” – the part of Western Sahara under the control of the Polisario (and in which the author of this blog has travelled extensively).

The Spiegel article goes on to tell us that Spain is eager to work with Morocco because of concerns about illegal migrants, many of whom cross Moroccan-occupied Western Sahara. Morocco routinely dumps illegal migrants in the desert in Western Sahara on the other side of its wall. These migrants (if they survive the desert) are picked up by the Polisario and accommodated until they can be repartriated (we met some migrants in this situation in November 2005, during fieldwork in the Free Zone). So much for cooperation with the Moroccan authorities in the name of sustainable and just solutions to the “problem” of migration.

Steinvorth then cites another Sahrawi member of the Royal Advisory Council, Brahim Laghzal, as stating that “Morocco, under its current king, is on a democratic path, and this [the autonomy plan] is our opportunity…. Autonomy is the only solution, as demonstrated by the Basques in Europe, the Catalans, the Scots and the Southern Tyroleans!” I’d be interested to hear from any Basques, Catalans or Scots to see if they think that their own versions of autonomy within a larger nation state have solved all their problems. This particular Sahrawi obviously hasn’t been following the electoral process in the UK, where the pro-independence Scottish National Party won a slim majority in recent Scottish parliamentary elections, catapulting their leader into the position of First Minister. Steinforth tells us that “He [Laghzal] believes that the separatists have gotten carried away and that the liberation movement, which was founded during the Cold War, has few democratic elements.” This is a subtle and juicy sentence that presses a number of buttons designed to make us feel less well-disposed towards the Polisario, and therefore to the idea of full independence. First, Steinvorth describes the Polisario as separatists, a term commonly deployed by the pro-Moroccan camp to suggest that the Polisario represent a troublesome minority who want to break away from an existing sovereign state. The reality is somewhat different – the Polisario existed before the Moroccan invasion, having fought the former Spanish colonial administration, and is an organisation dedicated to opposing a military invasion and annexation by an aggressive and expansionist neighbour with imperial ambitions. They are about as separatist as were the French resistance in World War II. Steinvorth goes on to tell us that the Polisario was founded during the cold war, clearly suggesting by association that the organisation is an anachronism, and perhaps attempting to associate the Polisario with communism. This is another common tactic of pro-Moroccan propagandists, who like to emphasise the links between the Polisario and Cuba – some pro-Moroccan groups in the United States go as far as claiming that Sahrawi children who have travelled to Cuba for their education have been “kidnapped by communists“. The third button Steinvorth presses in this sentence is the claim that the Polisario has few democratic elements, as opposed to Morocco, which his interviewee claims is on the path to democracy – “under its current king”. Whatever the democractic virtues or vices of the Polisario (which does at least claim to aspire to democratic national politics), this is somewhat rich – Morocco may have undertaken a process of reform, but the king retains absolute power and the nation will remain a hereditary monarchy. Hardly a good format for democracy. The flawed democracy that is the United Kingdom may have a monarch as its head of state, but at least day-to-day power is invested in elected representatives, even if these representatives do behave in a less than democratic manner once in power. The role of the Moroccan monarchy is more like that of the Saudi Monarchy (with which it has close links) than the constitutional monarchy of the UK. In recent months, Morocco’s reforming instincts have led it to ban YouTube, Google Earth and LiveJournal. Censoring of web access in Morocco seems to be driven by concerns that Moroccans might access material that is critical of the king or of the government’s policies on Western Sahara. The path to democracy is obviously a rocky one.

The role of Morocco in “modernizing” Western Sahara through investment is briefly mentioned, before we are treated to another Benmoussa quote in which he asks rhetorically “What is a Sahrawi?” This implicit questioning of the Sahrawi identity echoes the more forceful assertions by the Moroccan government and its foreign supporters that there is no such thing as a Sahrawi, and that the Sahrawi “identity” is a fabrication by a small group of “separatists”. Steinvorth, apparently paraphraasing Benmoussa, points out that the Sahrawi traditionally have been nomadic, wandering over an area that now straddles the borders of several countries in north-west Africa. The implication seems to be that as the Sahrawi are traditionally nomads, and did not concern themselves with national borders prior to 1975, it would be inappropriate for them now to have their own nation state. This seems peculiar given that across the world, hundreds of millions of people whose societies existed outside the context of the nation state for centuries or millennia, prior to the imposition of national borders by colonial and post-colonial governments, are now expected to live happily within those borders.

Towards the end of his article, Steinvorth erroneously cites the number of refugees in the Sahrawi camps around the Algerian town of Tindouf as 90,000. The number of refugees in the camps has been estimated by a number of independent bodies as at least 165,000, with some estimates as high as 200,000. 90,000 is the downgraded number of people “of concern” to the World Food Programme (i.e. requiring food aid) as of 2006. A senior member of a major international NGO told me late last year that she thought the WFP had reduced its figure as an excuse to cut food aid as a result of pressure from donors, who are using this aid as a political tool to pressure the Polisario into accepting Morocco’s autonomy plan (see earlier post on this topic). If this interpretation is correct, the WFP seems to be trying to starve the Sahrawi refugees out of the camps for political purposes, in support of an act of military aggression by one country against it’s neighbours (more evidence of Morocco’s diplomatic influence with key UN member states). The WFP figure of 90,000 people of concern is turning up in a lot of articles as representing the total number of people in the camps, either as a result of deliberate misinformation or sloppy research. Morocco certainly plays down the number of refugees, usually citing a figure of around 40,000. It is certainly in Morocco’s interest to downplay the number of people in the camps, just as it is to refer to the unoccupied territories of Western Sahara (known to the Sahrawi as the “Free Zone”) as its “buffer zone”, when it mentions this region at all. If only the refugees and the Polisario-controlled territories would disappear then Morocco’s annexation of Western Sahara would be so much easier. Normalisation of this annexation by friendly western powers would also be much more straightforward with no refugee problem or messy geographical partitioning to complicate the issue and throw the hypocrisy of Morocco’s “freedom and democracy” loving western allies into sharp relief.

Steinvorth does make the effort to appear even-handed, acknowledging torture and corruption on the part of Morocco and giving some space to the Polisario point of view. However, after the errors of fact and omission described above, and the extensive and sympathetic treatment of the Moroccan point of view, he ends his article with the following statement:

“For many, the idea that the roughly 90,000 refugees in Tindouf will ever return to an independent desert state is only an illusion. Over in Ajun, Mayor Uld al-Rashid is already preparing for the post-Polisario days.”

With this closing statement Steinvorth is asserting that the future of Western Sahara is a Moroccan one, under the autonomy plan that denies the Sahrawi the right to full self determination, ignores the pronouncements of the United Nations and the International Court of Justice, and runs counter to the position of the African Union. His article may not be as intemperate a statement of support for Morocco as the blatantly propagandist 2005 report from the Belgium-based European Strategic Intelligence and Security Centre, which presents many of the arrguments in the Speigel article much more forcefully. However, Steinvorth’s contribution seems to be part of the snowballing pro-Morocco propaganda campaign to prepare the citizens of Europe for the betrayal of the Sahrawi people in the name of political expediency and the dubious, fatuous “War of Terror”.

The endorsement of Morocco’s occupation will not make Europe safer, but will merely entrench an undemocratic and repressive regime that governs a country in which home-grown religious extremism is growing, fuelled by oppression, poverty and marginalisation. Unless Morocco is assisted in extending its occupation of Western Sahara into the Free Zone and dispersing or eliminating the Sahrawi refugees currently stuck in camps in Algeria, the normalisation of its occupation will not do anything to extend Moroccan control into the “empty space” of the Sahara where non-existent terrorists are said to be plotting the downfall of western civilisation. Assiting Morocco to extend its control into parts of the Sahara over which it currently has no jurisdiction (legal or otherwise) must by definition involve the fueling of armed conflict at best, and the endorsement of genocide at worst. Rewarding Morocco’s aggression by simply recognising its existing occupation will do nothing except increase the sense of desperation and hopelessness of the exiled Sahrawi, who will more than likely insist on taking up arms once again. However Morocco is rewarded for its imperial expansion, the result will not be an increase in regional stability, but an increase in regional tension and a likely return to conflict. With the inevitable influx of arms into the region in the event of renewed conflict, and the potential radicalisation of another group of people from whom hope has been snatched by political “realism”, this part of the Sahara will certainly be destabilised. Perhaps then the threat to international security will be real.

(1) Given that the UN is to a large extent simply the sum of its member states, and that UN policies and actions are determined by the interaction of its member states as they pursue their own interests, the lack of pressure on Morocco to agree to a free and fair referendum including the option of independence in Western Sahara is perhaps not surprising – Morocco has a lot more diplomatic clout than the Polisario.

(2) As a result of an agreement between Morocco and Israel to promote each other’s interests, a number of highly effective pro-Israeli lobby groups have now joined the propaganda war on the side of Morocco.

Posted by Nick Brooks

Posted by Nick Brooks